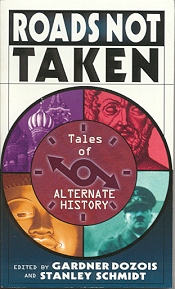

Roads Not Taken

Roads Not Taken Roads Not Taken

Roads Not Taken| In January, 1998, I was commissioned by Del Rey to

do some background research for an upcoming alternate history anthology, Roads Not

Taken, to be edited by Gardner Dozois and Stanley Schmidt. When I asked what

form the data should be sent, I was told it was up to me. My editor, Shelley

Shapiro, and I agreed that I would write an introduction which she could then choose to

use verbatim, in part, or simply mine for information. In any event, my name would

not appear in the anthology. I'm presenting my original introduction to the anthology here, along with a link to the introduction as it appeared when the book was released in July 1998. Roads Not Taken contains ten reprint alternate history stories from Analog and Asimov's magazines from such authors as L. Sprague de Camp, Harry Turtledove, Mike Resnick, Michael Flynn, Robert Silverberg, Gene Wolfe, A.A. Attanasio, Gregory Benford, Greg Costikyan, and Bruce McAllister. I'm rather happy that my first paying writer's gig put me in their company. |

|

"For of all sad words of tongue or pen,

The saddest are these: ‘It might have been!’"

-John Greenleaf Whittier

"Maud Muller" (1854)

The cry "it might have been" often reminds us all of bad decisions and opportunities lost. Would our lives be better if we had attended a different college, married a different spouse or taken a different job? We can never know. Whittier looked at these options with a sense of sadness for the alternatives which would never be achieved. Rather than look at these as the saddest words, other authors have elected to take up Whittier’s challenge and explore what might have been, turning Whittier's cry into the basis for alternate history.

Although nearly all historical fiction can be viewed as alternate history, after all, the reasons for the Duke of Buckingham’s assassination Alexander Dumas described in The Three Musketeers weren’t the reasons Buckingham was actually assassinated, the term usually refers to literature in which a change has been made which alters the course of history. If Dumas had not allowed Buckingham to be assassinated, The Three Musketeers could be considered alternate history.

The 1980s and 1990s have seen something of an explosion of alternate history. Throughout these decades, several original anthology series have been published which focus on alternate history, from Gregory Benford’s, "What Might Have Been" series (1989-1992) to Mike Resnick’s alternate themed anthologies (1989-1997). Reprint collections, like the one you hold in yours hands, are also available. Frank McSherry collected alternate World War II and Civil War stories in The Fantastic World War II (1990) and The Fantastic Civil War (1991). Anthologist Martin H. Greenberg has also been involved in several alternate history collections, such as Alternate Histories (1986) and The Way It Wasn’t (1996).

The recent growth of the genre is not merely in the realm of short stories. Several novels and series have been published during the same time. Orson Scott Card’s "Tales of Alvin Maker" series (1987-ongoing) features a realistic colonial-period America in which magic works. Stephen Fry’s Making History (1996) uses time travel to prevent the birth of Adolf Hitler. In the "Worldwar" series (1993-1996), Harry Turtledove altered history with an alien invasion in the middle of World War II. While authors are using a variety of these deus ex machinae to alter their worlds, other authors prefer to change history in a more mundane fashion. Stephen Baxter’s Voyage (1996), also a Sidewise Award winner, uses the survival of John F. Kennedy to create a more ambitious (and very different) space program which allows man (and woman) to reach Mars in 1986.

Literature is not the only realm which plays with history. In the 1980s and 1990s, alternate history could be seen weekly on television such as "Quantum Leap," which usually brought alternate history to the personal level or "Sliders" which used a multiple-world setup to examine the outcome of different historical change. In movie theaters, Marty McFly had to make sure his parents’ history had the proper outcome in the "Back to the Future" movies to avoid the world changing.

One of the things which make alternate histories fun to read is being able to spot exactly how the author changed history and debating whether the reader agrees the results are plausible or not. As with any other genre of literature, there are rules authors must use when writing alternate history. Once a change point is established, events should proceed in a logical manner from that point. A world in which China conquered Europe in the Roman period should show signs of Oriental culture rather than a continuation of modern civilization as we know it.

Authors will frequently bend the rules by including familiar figures, even if they can’t logically appear. In Richard Dreyfuss and Harry Turtledove’s The Two Georges (1996) several twentieth century figures still appear, although in altered and ironic situations. Part of the fun of these books is picking out these, or more obscure, anachronisms. In a well written alternate history, these can should be in-jokes between the author and readers who know the real history while other readers shouldn’t even realize they missed a joke.

"There were timelines branching and branching,

a megauniverse of universes, millions more every minute."

-Larry Niven

"All the Myriad Ways" (1968)

Alternate history is did not spring full blown from the minds of these authors like a latter day Athena. The earliest alternate history dates back to Louis Napol on Geoffroy-Ch teau’s French nationalist tale, Napol on et la conqu te du monde, 1812-1823 (1836). In this book, Geoffroy-Ch teau postulates that Napoleon turned away from Moscow before the disastrous winter of 1812. Without the severe losses he suffered, Napoleon was able to conquer the world. Geoffroy-Ch teau’s book must have been popular in France, for the subsequent years saw many similar novels published.

The first alternate history novel in English was Castello Holford’s Aristopia (1895). While not as nationalistic as Napol on , Aristopia is another attempt to portray a utopian society which never existed. In Aristopia , the earliest settlers in Virginia discovered a reef made of solid gold and were able to build a utopian society in North America.

Several more alternate histories appeared over the years, however the next major work, published in 1932, was perhaps the strangest anthology of alternate history ever assembled. A British historian, Sir John Squire, collected a series of essays, many of which could be considered stories, in If It Had Happened Otherwise from some of the leading historians of the period. In this work, Oxford and Cambridge scholars turned their attention to such questions as "If the Moors in Spain Had Won" and "If Louis XVI Had Had an Atom of Firmness." Four of the fourteen pieces examined the two most popular themes in alternate history: Napoleon’s victory and the American Civil War. Authors in this work included Hilaire Belloc, Andre Maurois and Winston Churchill.

The next year, 1933, would see alternate history move into a new arena. The December issue of Astounding published Nat Schachner’s "Ancestral Voices." This was quickly followed by Murray Leinster’s "Sidewise in Time." While earlier alternate histories examined reasonably straight-forward divergences, Leinster attempted something completely different. In his world gone mad, pieces of Earth traded places with their analogs from different timelines. The story follows Robinson College Professor Minott as he wanders through these analogs, each of which features remnants of worlds which followed a different history.

William Sell’s "Other Tracks" (Astounding 10/38), first postulated that travel into the past could effect history, but it took L. Sprague de Camp, writing in 1939, to fully explore what these changes could mean. Lest Darkness Falls deals with a modern man, Martin Padway, who suddenly finds himself in Rome in 527. Using his knowledge of Roman history and the twentieth century, Padway attempts to modernize Rome before Belisarius can sack the city.

De Camp followed Lest Darkness Fall with an even more ambitious alternate history: "The Wheels of If" (1940). While all the works mentioned have dealt with historical change, they have also limited themselves to the first few years after the change occurred. Although in "The Wheels of If," de Camp postulates a change in the outcome of the Synod of Whitby in 664, he does not begin his story until 1940, when Alistair Park suddenly finds himself in the body and life of Bishop Ib Scoglund of New Belfast.

"The Wheels of If" opened the floodgates. According to Robert Schmunk, perhaps the leading bibliographer of alternate histories, approximately 1,500 novels and short stories have been published since de Camp first began exploring the field, although there are probably many more published in foreign languages.

"If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the

others?"

-Voltaire

Candide (1759)

Although some of the earliest alternate history, such as Aristopia, attempted to portray utopian societies, most authors have not used alternate history as a means of creating the perfect world. Instead, many authors have chosen to use alternate history to explore the darker side of human existence. One of the most popular change points in the genre, a Nazi victory in World War II, is a perfect catalyst for this type of exploration.

The earliest alternate history to look at a Nazi victory was When the Bells Rang (1943), by Anthony Armstrong and Bruce Graeme. In this novel, the authors postulated a Nazi invasion of England in 1940. Although the English managed to fend off the Germans this time, the Germans would have many more successes in future alternate histories.

For instance, Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle (1962) looks at a world in which North America was divided between the victorious Nazis and Japanese in the aftermath of World War II. Minorities throughout the country are treated as sub-human, with the Germans and Japanese locked in an unsteady alliance which both sides are trying to turn to their own advantage.

While Dick’s world retains minorities to be abused, other authors have permitted the Nazis to eradicate minorities. When Robert Harris wrote Fatherland (1992), Hitler’s final solution was successful and the postwar Nazi government had managed to erase all knowledge of the camps. Harris’s book deals with the discovery by an inspector that something had happened to Germany’s Jews in the 1940s.

The other point of divergence many authors use is the American Civil War, with more than seventy stories and novels looking at a world in which the outcome of the Civil War was changed. Perhaps the most famous of these was Ward Moore’s Bring the Jubilee (1953) in which the South won the Civil War. Moore’s protagonist, Hodge Backmaker lives in a United States which hides in the shadow of the more successful Confederate States of America. A self-taught historian, Backmaker travels back in time to watch the battle of Gettysburg, influencing the outcome of the war.

The vast majority of alternate histories written take a more neutral stand on the changes which differentiate our world from theirs. The Two Georges depicts a North America still bound to the British crown after George Washington surrendered to King George III. Although the world the authors postulate is different, both technologically and socially from our own, the reader would be hard pressed to say whether it is better, with its lower crime rates, or worse, with poor labor relations, than our own world.

Wars are not the only points of divergence authors use to explore different worlds. Paul J. McAuley’s Pasquale’s Angel (1994), which won the first Sidewise Award for Alternate History, sees Leonardo da Vinci sparking the industrial revolution in the sixteenth century. John Kessel used a very different peaceful change to pit Fidel Castro against George Bush on a baseball diamond in "The Franchise" (1993).

The stories mentioned above, and the stories which appear within the covers of this book, will demonstrate that minor changes in history could produce widely divergent results. Even when authors start with the same point of divergence, their histories quickly lose any resemblance to each other. At their least, alternate histories provide entertaining reading and a place to begin debate. At their best, they spark historical research and raise questions about the nature of humanity.

| Purchase this book from |

Read the |

|

Enter the Alternate History Contest and win this and eleven other alternate history books. |

||